|

| The little stereoptican card that inspired a little mystery fun and opened the door to some historical research. |

|

| General Foch in 1921. |

The Short Story

In short, the glade is located where railroad tracks once met deep in a forest near the town of Compiègne, about 50 miles northeast of Paris. The site became memorialized by the French after WWI as the location of the signing of the armistice ending the war in November 1918. French General Ferdinand Foch is credited with the military defeat leading to the German request for the armistice. The signing took place in Foch's private railway carriage, which eventually became part of the memorial, housed in the building shown behind Shirer in the photo in my previous post.Twenty two years later the German army raced across France essentially unopposed and occupied Paris. It was France's turn to ask for an armistice, and Hitler took dramatic satisfaction in demolishing a wall of the memorial building, moving the car a few yards to the same location it had occupied in 1918, then sitting in the same seat that Foch had used as the terms of the armistice were read to the demoralized French representatives. Shirer observed the proceedings and made a dramatic radio broadcast, somehow not only scooping the other news services by several hours, but the German broadcast of the event as well, to the fury of the German high command.

.

|

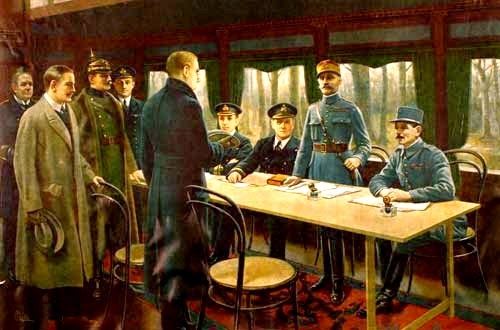

| November 11, 1918 - German representatives arrive in Marshal Foch's private railway carriage parked deep in the forest of Compiègne to accept the terms of the armistice ending WWI |

The Rest of the Story

Amistice of 11 November, 1918

.jpg) |

| Marshal Foch stands withother French officers and representatives in front of his private railway carriage just prior to the signing of the armistice ending the hostilities of WWI |

|

| Logo of Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits |

The site became a memorial to the defeat of Germany, and included a statue of Foch, the building housing the railway carriage, the Alsace-Lorraine Memorial, and a granite block in the center of a circular concrete slab marking the actual location of and commemorating the signing of the WWI armistice.

|

| German representatives to the signing were carried overnight on a French train, which arrived at dawn at the glade. One can imagine the crunch of boots in the snow and the icy breaths as the German officers with spiked helmets walked to Foch's carriage in the adjacent train, while the steam engines hissed and chuffed. |

The final treaty drawn up, known as the Treaty of Versailles, was a disappointment to Foch. Because Germany was allowed to remain a united country, Foch declared, "This is not a peace. It is an armistice for 20 years". The second world war began 20 years and 65 days later.

Armistice of June 22, 1940

William L. Shirer, a war correspondent for CBS radio, arrived in Paris on June 17, 1940. In his book, Berlin Diary, Shirer describes a city deserted on the otherwise lovely June day, "which, if there had been peace, would have been spent by the people going to the races at Lonchamp or the tennis at Roland Garros, or idling along the boulevards under the trees, or on the cool terraces of a cafe". But the Germans had entered the city a few days before, after sweeping nearly unopposed across France, and it was "utterly deserted, the stores closed, the shutters down tight over all the windows." Parisians had fled in panic at the approach of the Germans, choking the roads leading from the city. A huge swastika floated from he Eiffel Tower.

But the arriving German soldiers turned out to be not rapists, but generally polite, acting as tourists with cameras around their necks, and even taking off their caps at the tomb of the unknown soldier. Germany encouraged and assisted foreign war correspondents, eager that their exploits be reported to the world. So on June 19, Shirer and other correspondents were taken to Compiègne - an armistice between France and Germany was to be signed in the same place as the signing of the 1918 armistice.

My view of the timing of events is a bit murky, based on comparing Shirer's book to the photograph. He says that when he arrived at Compiègne at 6:00 PM on June 19, "German army engineers were feverishly engaged in tearing out the wall of the museum where Foch's private car in which the 1918 sarmistice was signed had been preserved ... before we left, the engineers, working with pneumatec drills had demolshed the wall and hauled the car out of its shelter". And yet the photograph of him typing does not show the wall as having been demolished. On the other hand, there are differences in the appearance of the building from the photo showing the car emerging. Perhaps we are looking at different ends of the same structure. Shirer also puts the date of the signing at June 21, whereas all other sources use June 22, 1940.

At any rate, by June 22, 1940, the famous railway carriage, now to become even more renowned, had been removed from its museum and placed on the spot where the WWI armistice had been signed in 1918. Hitler arrived in the afternoon with others of the high command to stomp around, looking with scorn at the various monuments and memorials. The scene was reported by radio by Shirer that evening, and a transcript may be found at http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/francesurrenders.htm. Shirer's dramatic radio broadcast somehow not only scooped the other news services by several hours, but the German broadcast of the event as well, to the fury of the German high command. Following the signing the railroad car was moved to Berlin where it was eventually destroyed. Hitler also had all the monuments and memorials at the glade destroyed, with the exception of the statue of Foch.

The glade of the Compiègne memorial was eventually restored by France after the end of WWII. An identical Compagnie des Wagon-Lits carriage, no. 2439, built in 1913 in the same batch as the original and present in 1918, was renumbered no. 2419D (the number of Foch's original railway carriage), and installed in a new Clairiere de l'Armistice.

.

|

| The Compiègne Wagon being removed from theClairiere de l'Armistice on June 19, 1940. |

But the arriving German soldiers turned out to be not rapists, but generally polite, acting as tourists with cameras around their necks, and even taking off their caps at the tomb of the unknown soldier. Germany encouraged and assisted foreign war correspondents, eager that their exploits be reported to the world. So on June 19, Shirer and other correspondents were taken to Compiègne - an armistice between France and Germany was to be signed in the same place as the signing of the 1918 armistice.

My view of the timing of events is a bit murky, based on comparing Shirer's book to the photograph. He says that when he arrived at Compiègne at 6:00 PM on June 19, "German army engineers were feverishly engaged in tearing out the wall of the museum where Foch's private car in which the 1918 sarmistice was signed had been preserved ... before we left, the engineers, working with pneumatec drills had demolshed the wall and hauled the car out of its shelter". And yet the photograph of him typing does not show the wall as having been demolished. On the other hand, there are differences in the appearance of the building from the photo showing the car emerging. Perhaps we are looking at different ends of the same structure. Shirer also puts the date of the signing at June 21, whereas all other sources use June 22, 1940.

At any rate, by June 22, 1940, the famous railway carriage, now to become even more renowned, had been removed from its museum and placed on the spot where the WWI armistice had been signed in 1918. Hitler arrived in the afternoon with others of the high command to stomp around, looking with scorn at the various monuments and memorials. The scene was reported by radio by Shirer that evening, and a transcript may be found at http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/francesurrenders.htm. Shirer's dramatic radio broadcast somehow not only scooped the other news services by several hours, but the German broadcast of the event as well, to the fury of the German high command. Following the signing the railroad car was moved to Berlin where it was eventually destroyed. Hitler also had all the monuments and memorials at the glade destroyed, with the exception of the statue of Foch.

|

| Left to right: Joachim von Ribbentrop, Walther von Brauchitsch,Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler, and Walther von Brauchitsch in front of the Armistice carriage |

.

|

| Hitler at the Wagen von Compiègne |

.

|

| Hitler (hand on hip) looking at the statue of Foch before signing the armistice at Compiègne, France (22 June 1940) |

After WWII

The glade of the Compiègne memorial was eventually restored by France after the end of WWII. An identical Compagnie des Wagon-Lits carriage, no. 2439, built in 1913 in the same batch as the original and present in 1918, was renumbered no. 2419D (the number of Foch's original railway carriage), and installed in a new Clairiere de l'Armistice.

.

|

| Marshal Foch statue |

,

|

| A granite memorial marks the exact location of both armistice signings. The building in the background is a museum housing a replica of the original railcar. |

This is a very interesting entry, Tony! I'm particularly impressed by the symbolisms: an armistice signed in the middle of nowhere, inside a converted railroad car, which was then kept as a memory of a proud moment, only to be turned into a new symbol, with the signing in the same car, in the same place, of a new armistice, this time having Germany as the proud victor.

ReplyDeleteFor what I've read, Hitler was a man who really understood the value of symbols, so in that sense it might not be as surprising that he had the old carriage pulled from the museum to give closure to the old defeat of his country; what surprises me (and then, not really) is that the car was eventually destroyed. Do we know if it was destroyed during one of the many Allied bombings on Berlin? Or it was destroyed by the Germans?

That's a good point about the symbolism, Miguel. Foch used it also, by performing the signing on "The 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month" of 1918. It would seem that maintaining support to make war takes marketing skills akin to keeping the public in a frenzy over the latest iPhone! Certainly Germany put some effort into supporting foreign correspondents, as long as they told the story the Nazi's desired. After Compiègne Shirer spent the next year in Berlin, where he was initially supported in his efforts to report the war. But censorship became tighter, to the point that he discovered he was on a list to be arrested as a spy, and he needed to leave.

ReplyDeleteThe railway carriage was kept as a souvenir by Germany, but was destroyed by the Nazi's (according to the sources I found) by dynamite and fire toward the end of the war, with the Nazi's claiming allied bombing.

Fascinating post, and I love all the photos. Thank you so much for sharing.

ReplyDeletefascinating entry, thank you very much.

ReplyDelete